Lina Wertmüller: The Forgotten Story of Cinema's First Female Best Director Nominee

As Greta Gerwig misses out on a nod for Barbie, let’s look back at Lina Wertmüller and the "grotesque vaudeville show" of a film that sealed her place in Oscars history. Did the Academy get it wrong?

In the 96 years that the Academy Awards have been held, only eight women have been nominated for Best Director. If you’re like me, you might assume that the first was Kathryn Bigelow or Jane Campion, two filmmakers who have been making hard-hitting, occasionally testosterone-laced dramas for decades. But you’d be wrong. The first was a European arthouse auteur known for stylistically bombastic political satires that walked a fine line between art and exploitation. So what was the film that got her noticed by the Hollywood establishment, and why did they nominate it? The tale of Lina Wertmüller, Seven Beauties, and the Oscar nod demonstrates one of the Academy’s most consistent flaws. And it isn’t the one you think.

Lina who?

Born Arcangela Felice Assunta Wertmüller von Elgg Spanol von Braueich (seriously) in Rome in 1928, Lina Wertmüller was an unlikely candidate to become a socialist arthouse darling. She came from Swiss-Italian aristocracy, but defied her family early on by immersing herself in Flash Gordon, getting kicked out of multiple Catholic schools, and becoming a traveling puppeteer instead of a lawyer. During her touring years, she befriended actress Flora Carabella, who, through husband and Italian cinema royalty Marcello Mastroianni, introduced the young puppeteer to director Federico Fellini. She would go on to become his protégé and the Assistant Director on 8 ½, a film often cited as one of the greatest of all time.

“Federico was a magician to me,” she told Interview in 2017, “[A] real poet of the images. You can't learn from an ingenious talent like him, but you can certainly admire his way of working.”

“I love grotesque poetry, and I think my films have that style, which combines humor and drama, irony and cynicism, comedy and tragedy.”

- Lina Wertmüller

And yet, she did learn. Wertmüller’s films possess the same cacophony, leering gaze, and extravagance that Fellini’s have, though she grounded her stories in politics more than fantasy. Her directorial debut, 1963’s The Basilisks, fell squarely within the bounds of neorealism, a style that dominated Italian cinema in the postwar years and focused on meandering depictions of the working class. Soon, however, she pivoted to a more anarchic style that would come to define her career. Bursting with blithe misogyny, lust, satire, color, and noise, her movies are pure tonal chaos, lurching from comedy to atrocity at a head-spinning clip.

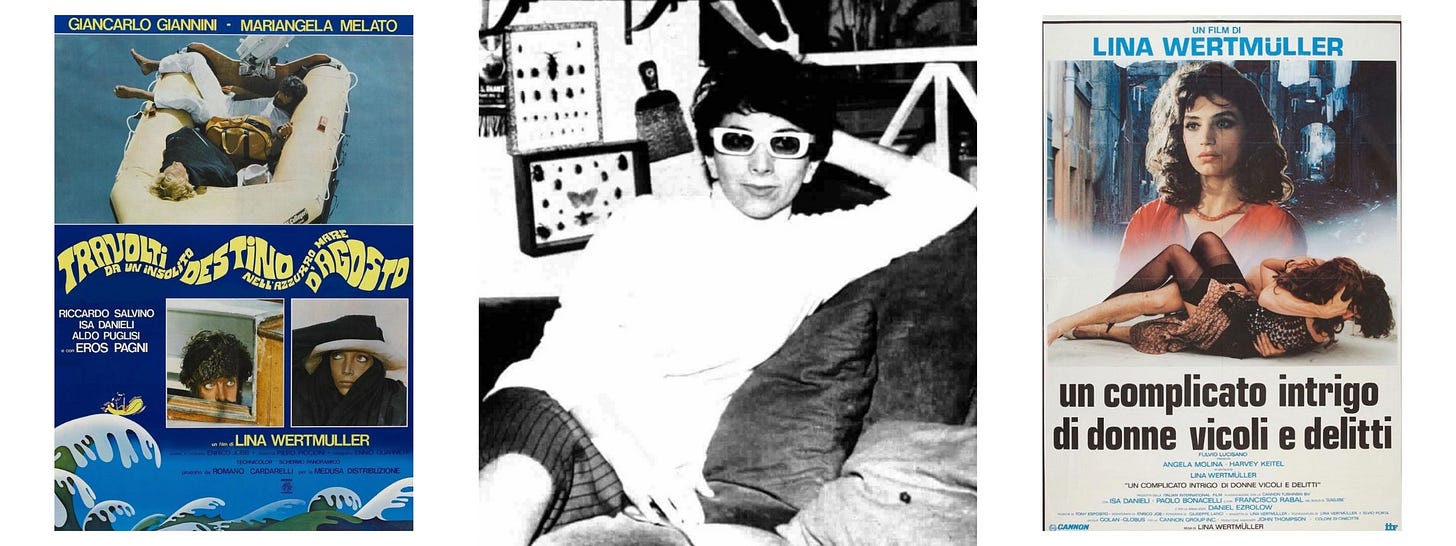

The Seduction of Mimi (1972), Love and Anarchy (1973), and Swept Away (1974), (later remade with a shambolic thud by Guy Ritchie and Madonna) launched her onto the international stage. All of them star Italian matinee idol Giancarlo Giannini and all of them feature Wertmüller’s kinetic swirl of voices, action, and moods.

“I love grotesque poetry,” she told Criterion in 2017. “[A]nd I think my films have that style, which combines humor and drama, irony and cynicism, comedy and tragedy. It allows you to play with different narrative tones and rhythms. It's more than a style – grotesque narrative reflects my own personality.”

Nowhere is this more evident than in the film that earned her the first-ever Academy Award nomination for a female director, 1975’s Pasqualino Settebellezze.

Seven Beauties

Rebranded as Seven Beauties in the U.S., Pasqualino Settebellezze begins just before World War II and tells the story of Pasqualino (Giannini again), a posturing, suited little dandy from Naples with an Inspector Clouseau mustache and illusions of grandeur. He’s trying to keep his seven sisters in line, though none of them need intervention. Makeup, costumes, and Wertmüller’s pitiless camera let us know that these women are supposed to be hideous blights on femininity, but they earn a living and fend for themselves, something that Pasqualino, who trots around town in noisy leather loafers pinching women’s asses and leering at pre-pubescent girls, cannot claim. After discovering that one of his sisters is engaging in sex work, he murders her pimp and bungles the aftermath, plowing straight through all the wrong doors and ending up (brace yourself) in a Nazi concentration camp. There, he does what he has to to survive, and trust me when I tell you that it makes the blood curdle.

Surfing the ‘70s zeitgeist

The ‘70s were both a turning point for the film industry and a mercifully short-lived chapter. Deliverance, The Deer Hunter, Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom, and I Spit On Your Grave (to name a few) proved just how brutal a medium cinema could be, but filmmakers – and society as a whole – lacked the language and awareness to make sense of the savagery and anguish. As a result, these movies are groundbreaking examples of how to torture an audience, but leave you with little to grapple with. They are largely devoid of analysis or self-reflection, onslaughts of punishment without reckoning.

Seven Beauties is, by comparison, fairly tame, but it is still unmistakably of its time, somehow managing to graphically depict the Holocaust and overlay it with peppy irony. The opening scene features several minutes of real-life footage of the war – explosions, corpses, Mussolini – backed by a surreal, ironic sermon of a song punctuated by “oh yeahs.” (It’s a narrative device that Spike Lee has made famous, but which, as this movie proves, Wertmüller pioneered). In another scene, prisoners shuffle through rooms clouded with the ashes of cremated bodies while the histrionic strains of Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries” boom in the background. Naked corpses, the rape of a woman bound and gagged, and a man diving headfirst into a tank of human feces is just the tip of the iceberg for this film. These scenes are horrific and unflinching, but Wertmüller undercuts them with comedy, jolting from horror to farce to horror without pausing to assess the damage.

“ She says she has a penchant for the grotesque, but that is not the same as having a talent for it”

- Pauline Kael

Roger Ebert was taken in by the incongruity, calling the film “opaque, despairing, and bottomless,” and demonstrating Wertmüller’s “mastery of filmmaking.” Pauline Kael, whose influence as a film critic trumped Ebert’s at the time, disagreed, calling it “a grotesque vaudeville show” and “a theater of garbled ideas.” She even pointed out that Wertmüller’s claim of having a penchant for the grotesque was “not the same as having a talent for it.” The film also fell afoul of Holocaust survivor and influential psychologist Bruno Bettelheim, who published an essay in the New Yorker calling it a fascist portrayal of Fascism.

Preaching to the choir

Despite its divisiveness, Seven Beauties was catnip for the directors branch of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, which was nearly a decade into a giddy love affair with subversive young filmmakers who were defining the New Hollywood and Europe’s New Wave. After 40 years of fawning over the dons of the studio era like Frank Capra and William Wyler, they were nominating the likes of John Schlesinger (for Midnight Cowboy), William Friedkin (for The French Connection), and Ingmar Bergman (for Face to Face).

“I consider myself a director, not a female director. I think there’s no difference.”

- Lina Wertmüller

Seven Beauties was in the mold of these films, full of swagger, style, and, of course, the Oscars’ favorite topic, World War II. In addition to Best Director, it was nominated for Best Foreign Film, Best Actor (for Giannini), and Best Screenplay (Wertmüller), but the director insisted that the acclaim meant little to her at first, telling Variety in 2018, “[i]t was the media reaction that made me realize how significant my nomination was. Since I was in the U.S., I was flooded with interview requests from TV networks and newspapers. Someone told me that news reports were trumpeting the nomination as though it were a historic event. Actually, in hindsight, it was, especially for women all over the world.” Of her role as female director, however, she was dismissive. In a 2017 interview, she remarked, “I’ve never endorsed the feminist movement. I consider myself a director, not a female director. I think there’s no difference. The difference is between good movies and bad movies. We should not make other distinctions.”

Time plays games with legacy

After the film’s success, Wertmüller was a celebrity for a while. Laraine Newman performed a recurring rendition of her on Saturday Night Live (trademark white-rimmed glasses included), and Warner Bros. gave her a contract to make four films. However, after the first film sank at the box office, the studio rescinded the contract. She continued working, but none of her later movies reached the level of success that she earned in the ‘70s. Still, she was optimistic about her legacy. “It's always been seen in the history of culture that certain works were understood afterwards,” Wertmüller told The Washington Post in 1984 after another box office dud. “The perspective came afterwards.”

“Wertmüller…has a stunning visual intelligence accompanied by a great confusion of mind”

- Michael Wood

From a 2024 perspective, Seven Beauties is bold, visually arresting, and ultimately impenetrable. It is bewildering but not thought-provoking; comedic but hard to laugh with. There is no question that Wertmüller’s work oozes panache, but the political stridency that weaves its way through the film is both obtuse and lacking cohesion, which likely prompted Bettelheim’s assessment that it was a fascist film about Fascism. To put it more overtly, Michael Wood wrote in The New York Review of Books in 1976 that “Wertmüller…has a stunning visual intelligence accompanied by a great confusion of mind,” and, “Her movies always look good, they seem to be about things that matter, and they are finally so muddled that they put up no resistance to — indeed even invite — the most contradictory and admiring interpretations.”

We’re all obsessed with the idea of firsts – first person to walk on the moon, first talking picture, first female president (oh, wait…) – but sometimes, the firstness of it all gives the thing itself an outsized weight. Seven Beauties is a chaotic, stylish, belligerently slippery film that ended up making Wertmüller the first female nominee for Best Director. The fact that it’s not on constant rotation on Mubi or the Criterion Channel isn’t further evidence of the devaluing of non-English language films or female filmmakers, it just isn’t a film that holds up as well as, for example, Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, a movie that was eligible for the Oscars in the same year as Seven Beauties but was criminally (though not surprisingly) overlooked. Jeanne Dielman is now considered one of (if not the) greatest movies of all time, and is a film where the perspective, to quote Wertmüller, “came afterwards.” The initial, mixed reception of Seven Beauties, in contrast, was pretty spot on.

The teeny tiny gold man

…Which brings us back to the elephant in the room about the Oscars: they rarely get it right. Yes, Greta Gerwig should have been nominated for turning an explosion of color, capitalism, and internalized cultural misogyny into a coherent and sprightly box office juggernaut, but when the same organization deems Driving Miss Daisy to be the best film on planet Earth in 1989, or, even worse, its spiritual remake Green Book 30 years later, it’s hardly worth griping about.

The Academy throws a good party and shines a brief spotlight on buzzy movies and filmmakers, but, as Wertmüller and Chantal Akerman could attest, it doesn’t determine whether a legacy shrinks or expands over time, even for nominees who are “firsts.”